WILD WORDS v1.0

THE CONVERSATION

CORE SYSTEM

The Basics

- The conversation describes and encapsulates the dynamic at play at the actual gaming table (or medium of your choice). When and how players talk to each other to get things done, and what elements of the game, rules, and world they control.

- It's a natural part of playing a TRPG that all but the newest players will be familiar with, but there are still a few conventions that the Wild Words engine follows in this regard.

- At its core, think of the conversation as the action of playing the game itself - a verbal exchange that drives a narrative forward.

What Is The Conversation For?

Telling stories! But also bringing the narrative to places where it interacts with the rules.

There's nothing wrong with collaborative storytelling, but the Wild Words Engine has rules for a reason - they help to direct play, to solve problems, to offer opportunities, to define limits. The conversation is what brings those rules into play, and helps reinforce them.

As an example, most scenes in Drift are narratively quite free. Players have their characters explore the world, interact with NPCs, and generally move the story of the game along at their own pace. But when one of them wants to have their character do something difficult, dramatic, or dangerous, the rules need to come into play. The rules are introduced to the fiction, and the conversaton containing them continues.

Flags

A flag is the idea of a player signalling that they want something in particular to happen, which can help the GM and the other players adapt both the conversation and the general narrative of the game to fulfil those wants. If someone describes how their finger is on the trigger, and they're ready for anything, they probably don't want a leisurely stroll through the park. If your game is all about leisurely strolls through the park, they're likely going to be disappointed.

Make the kind of experience your game offers as clear as possible - through art, through text, through GM advice and resources, and particularly through character options. It makes flags easier to read and react to in play.

Control

This can be a tricky thing at times, but it's absolutely essential for smooth play - as a designer, you need to know which elements of the game are controlled by which people at the table. Narrative control is usually weighted toward a GM figure, and moment-to-moment decisions toward players with characters, but this doesn't necessarily need to be the case.

For example, many systems have a GM in control of almost every aspect of the narrative that isn't touched on by direct character actions. The Wildsea doesn't do this - it specifically includes systems that spread some narrative agency around the table in terms of establishing fictions and truths about the setting, and sometimes even an immediate locale.

It's also useful to work out if there are any mechanical elements of a game that might be treated in an unexpectedly narrative-first fashion, or vice-versa. All but the newest players come to the table with a lot of preconceptions, and knowing how your rules will appear (and how easily they might be followed) by particular styles of player can have an impact on the raw playability of your game.

Though damage and injury in The Wildsea are handled mechanically, character death is an explicitly narrative event that's completely under the control of a character's player. If it's not the right time for a character to die, they don't - as far as the Wildsea is concerned, moments with such gravity should always be in service of the story, not potentially in spite of it.

Focus

The 'narrative spotlight' of the conversation, focus passes from player to player as they interact with the world. it can also be held by the GM when they're describing things, playing NPCs or enforcing rules (or just joining in with the general chatter at the table - the GM is as much of a player as anyone else, just with a different set of resources!).

Focus moves naturally from player to player, but a GM can direct it at a particular individual if they need to. Similarly, as a designer you can direct and control focus by writing rules that rely on it. The most common of these would be a fixed initiative system, perhaps determined by a stat or roll, for a given scene - if characters act in a particular order, focus moves in that order as they speak.

That said, Wild Words treats focus as an inherently pretty fluid thing, If a GM needs a way to 'balance' time in the spotlight, especially for high-stakes situations like combat or chase scenes, there's the option to use a Focus Tracker (a subsystem that combines the core systems of focus and tracks, described on page XX).

Hijacking Focus

You might also write abilities that allow focus to be 'hijacked' - taken away from another player or element of the world if a specific condtion is set. Unless you're intending on making a very adversarial game, we recommend...

- Players having focus hijacked from them by another player have to agree to it

- The focus always returns to whatever it was hijacked from when the hijacking is finished

SCENES

CORE SYSTEM

The Basics

- Scenes divide play into recognisable chunks, like the scenes of a movie, play, or episode of a TV show.

- A game can have different types of scenes, which might encompass different periods of time, require different kinds of actions or decisions from players/GM, or run on different rules and mechanics

- Scenes can help to establish a loop of activities for a game, or merely serve as breaks between bits of action or story.

Do I Need Different Types of Scene?

When creating a Wild Words game, one of the first things you need to consider is what kind of activities the game focuses on. The more important an activity is, the more likely it will have unique mechanics that govern. The more unique mechanics that apply, the more likely it is that players will find the action and rules easier to follow if those rules are limited to a particular type of scene.

Using Wild Words to create Streets By Moonlight, a game of cthulhuesque cult investigation and growing madness, will likely focus on those elements of play above all others. It has a specific type of scene dedicated to gathering and processing clues, another to represent a raid or the exploration of a significant location, and another for dealing with the growing challenges to the sanity and stability of the characters in the wake of their experiences. The Wildsea is a game of exploration and survival on an endless treetop sea. As well as general scenes that handle most of play, the game defines two additional types of scene; Montages, that handle larger complex actions and periods of downtime with a single roll or stated intention, and Journeys, which focus more on the ship that the characters share, using it to travel the rustling waves in a far more structured way than a normal scene would allow.You might have a particular scene and set of rules, conventions or unique mechanics to govern...

- Combat and times of high tension

- Periods of downtime, study, or exploration

- Sections of in-character worldbuilding

- Time spent travelling from place to place

- Moments of relaxation and healing

- Time spent building up a base, hide-out, or home

Establishing a Loop

When using different types of scene, you may want to aim to create a loop - a set structure that the game follows, something to mold the story and action of play around. You might choose...

A Core Loop

This sets scenes as happening in a specific order, so players always know what's coming next. Core loops hold structure first and narrative second - the story is still important, but it will follow a particular set of repeating beats.

Streets By Moonlight follows a core loop - characters have time to prepare and investigate, then to confront whatever they've discovered, then to recover from in the confrontation's aftermath. Once sufficiently recovered (or perhaps before), a new investigation begins.A Fluid Loop

With this method specific types of scene will reoccur, but in an order that is dictated by the narrative. This puts the story and the decisions of the players and GM at the forefront of an experience, but might be more difficult to balance mechanically (as certain characters may be better suited to a particular type of scene, but the story could lead play away from those scenes occuring often).

The WIldsea follows a fluid loop - basic scenes, montages, and journeys happen whenever they feel most appropriate, allowing variable length and frequency of different modes of play. A session may be a series of linked basic scenes, with no special mechanics, or it might be a single long journey, or anything in between.Why Use Scenes?

Humans tend to split things into digestible chunks by nature, especially narrative. Shows have episodes and switch focus from one group of characters to another, books have chapters and differing viewpoints. Scenes in Wild Words simply codify the way a lot of people already play, allowing for groups of complementary mechanics and easy key phrase uage.

Complementary

One of the easiest ways to define a scene is by restricting or delineating the kinds of mechanics used within it. This allows you to use mechanics to change the flow of a game and the focus of a table.

A Montage in The Wildsea is a particular type of scene that runs very differently from usual play. Instead of taking actions in any order, as the narrative dictates, each character has the opportunity to undertake a single Task - a larger, more complex action that's boiled down to a single description or dice roll. Once every character has taken a task, the montage ends and the next scene begins (usually based in some way on what was accomplished during the montage).If you do use scene-specific mechanics, we recommend keeping them in the same ballpark as the rest of the game in terms of how they work. If every other roll in the game treats high results as better, for example, don't have high results mean something bad in one particular type of scene.

Key Phrases

When thinking of abilities and rules, the various types of scene in your game can act as keywords for easier understanding and for setting durations. An ability might say, for example...

- ... Until end of scene.

- For the duration of a scene...

- During a ____ scene, you can...

TRACKS

CORE SYSTEM

The Basics

- A track is a named string of boxes or circles that are filled, or ‘marked’, to measure progress towards an event, accomplishment, or danger.

- They're one of most fundamental and flexible tools you can use when designing a Wild Words game.

- Impact relates to how many boxes are marked at a time, especially when character actions are involve

What Are Tracks For?

Anything iterative that either the players or GM need to keep track of.

Tracks are an excellent visual reminder of change or opportunity. When creating a Wild Words game, think about what elements of the game you want tracks to be integral for, and also which situations you'd suggest a GM uses them in.

Some common elements for an integrally used track are...

- The uses or resilience of aspects

- The attributes or benefits of a shared asset

- The time until an impulse takes effect

- The health or potency of a hazard

- The health, stamina, stress, or magic of a character (Core Wild Words assumes these are handled by the tracks on aspects, but individual tracks can handle these elements if you're aiming for a more traditional TRPG experience)

Tracks are also an excellent GM tool. Consider advising GMs to use tracks to aid in keeping track of certain elements of the world, which might be marked by...

- A character's actions

- The passage of time

- The results of a die roll

- A decision made

- The use of a resource

- Events in the wider world

- An advancing story or plotline

Marking a Track

Marking a track is as simple as putting a line through one of the boxes. It usually represents the idea thatsomething has happened, and that whatever it was is leading up to a bigger something. The bigger something will usually be prompted by the final box on the track being marked.

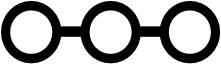

Taming the Megashrew

Taming the Megashrew

Taming the Megashrew

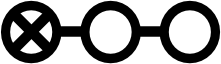

Burning a Track

If you want the game or GM to be able to mark a track permanently, or at least with something extremely hard to remove, the option to burn a box on a track is there too. This is shown with a cross through the box rather than a slash, and represents a change that's almost impossible to undo (or that would take significant effort or serious narrative attention).

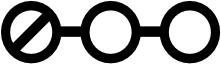

Here's a partially burned track.

Taming the Megashrew

Clearing a Track

Marks on a track are temporary - they can usually be removed in some way (by healing if a track represents damage, for example, or by passing time if a track represents something that needs constant upkeep). To clear a mark on a track, simply erase the line that goes through the rightmost box.

For some tracks, like those on a character sheet, this removal of marks is often as important as how they're made. For other tracks (like one leading up to the start of a local festival) you might simply remove the entire track once it's fully marked, and not worry about how a single mark might be cleared.

As an example, once the megashrew is tamed your rules might offer the GM an option - is the track removed, and the beast remains tamed for the forseeable future, or is the track kept despite being fully marked, representing the possibility of the creature returning to a wilder state as passing time or specific actions clear some of those marks? In the second example, giving the players the ability to burn a box on the megashrew's track would ensure it would likely never return to a completely savage state, even if marks started getting cleared.As a good rule of thumb, clearing a mark from a track should be a little more difficult or in-game-time-consuming than making one. For example, if a character uses an action to mark a track, removing that mark might take an action plus a resource of some kind. Basically, reversing a change should usually be a little harder than making it (though this is, of course, situational).

While clearing a mark should be relatively easy, clearing a burn should be something as memorable as the burn itself, and should usually take a significant amount of additional effort. This might come in the form of...

- A small quest or specific activity aside from the main narrative

- The use of a particularly rare or limited resource

- An effort from every character working together

- An achievement that means something to the character

Track Length

If tracks are intended to be marked one or two boxes at a time, the following rough guide should help.

1-2 boxes: Likely to be filled by a single action roll or event in the world. Not meant to hang around for long.

3-5 boxes: Will need multiple things happening, usually, to end up fully marked. Good for elements of a character, such as aspects.

6+ boxes: Will usually define something for a good amount of time, and take multiple interactions to fill

If multiple boxes on a track can be marked at once, especially if that track represents an obstacle players are trying to bypass or a threat from the world that needs to feel hefty, double or triple these values. This gives you a track that can withstand multiple instances of increased impact, and that might be suitable for track breaks.

Open, Hidden, or Secret?

As a designer you'll need to decide how much information players know about the tracks that are in play.

An open track can be seen by anyone at the table, and are most often found on character sheets and scribbled down on pieces of paper to track world events that the players have a good amount of knowledge about.

A hidden track can only be seen by one person, usually the GM. These are most often used for things like the health of an NPC or the resilience of a hazard, where the effect the characters are having need to be recorded but you don't want them to know how close they are to a 'win' to avoid spoiling the surprise.

A secret track can usually only be seen by the GM, and the players don't know it exists.

In Streets By Moonlight, the big bad of a campaign grows in power as the investigators try to discover and stop it. This growth is known to the players, but how much time they have left is hidden... until they're close to the end.Track Breaks

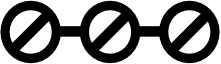

Track breaks allow you as a designer (or the GM) to create tracks representing multiple states of a situation, or to combine what would have been several small tracks into one longer track. For example, the tracks...

Might be combined into a single track...

When there are no marks on the track, the situation is calm. When the track is first marked, the early warning signs of an earthwuake appear. The players will have time to react to these before the second mark is made, upon which time the track break is reached and the earthquake truly begins. The third, fourth, and fifth marks cover the duration of the earthquake, with the event ending after the fifth mark is made.

Track breaks save space and offer options, both in terms of tracking narrative and in terms of creating a more complex mechanical base for your game

Gauges

A special kind of track that has an associated level, gauges are useful in situations where a track filling will have ongoing, but not permanent, effects. A gauge might look something like this...

Stress

In this example, the stress gauge has no boxes filled and stress is sitting at level 1. If all of the boxes are filled, the stress level might increase to 2 - perhaps a character now has a mechanical penalty due to their growing stress, which remains until they can decrease that stress level to 1 (or even zero). Boxes are cleared so the track can be filled again.

In Drift, the Paradox Gauge tracks how much a character has been affected by the weirdness of the city. every time the paradox gauge goes up a level, they take a special kind of injury that can only be healed through a particular in-universe event.Ratings

A way to tie tracks into a game's dice system, a rating is a track that allows a specific number of dice to be rolled depending on the amount of boxes it has and whether those boxes are filled or not

Here's an example...

Speed

If a character wanted to roll something related to speed using this rating, they's usually roll 3d6 (dice equal to the number of boxes on the track.) However, in the above example one of the boxes is marked - because of this, the character would roll 2d6 instead (dice equal to the number of unmarked boxes).

Rating allow you to vary dice rolls depending on how a track interacts with a situation. You might even have it so that a certain part of the rules allows a player to roll dice equal to how many marks there are on a track instead. Be careful with ratings - anything above a six-track has the capacity to allow players to roll a doce pool that will always result in doubles.

In The Wildsea, a crew's ship has six ratings. They start with one box on each track, and the way a ship is constructed allows them to gain five additional boxes. Ratings rolls allow a player to roll dice equal to the unmarked boxes on a rating, to determine how well the ship performs in a certain situation related to that rating. In Streets By Moonlight, a character has a rating to track their Insight - the level of understanding they have when it comes to the occult forces that secretly run their city. Marks on this track represent their deepening knowledge, but filling the track also represents their dwindling sanity. An Insight roll allows them to roll dice equal to the number of marks on an insight track, turning their horrifying realizations into a useful source of information.DICE, POOLS, & ROLLS

CORE SYSTEM

The Basics

- Wild Words runs on a dice pool system, where multiple elements controbite dice to a pool, which is then rolled for a set of results. The highest result (usually) is the final outcome of a roll, though other results may also play a part

- Core Wild Words assumes a dice pool of d6s, with a maximum number of six dice (thus ensuring that doubles are never a complete certainty).

- Dice only come into the game as a response to uncertainty or drama - there's a rule of three Ds that you might find it useful to stick to in the text below

What Are Dice For?

Bringing an element of randomness to proceedings.

When the outcome of an action or event is uncertain, it's time to roll some dice. There are other situations you might choose as a designer for dice to come into play, of course, but this is the easiest guideline.

This can be clarified further with a reference to the three Ds, three situations in which players will likely want to be rolling dice.

- When a situation is Dangerous, so they can partake in the thrill of uncertainty.

- When a situation is Difficult, so they can show off how they've made their character to tackle such difficulties.

- And when a situation is Dramatic, so there's an element of added tension.

There's a fourth situation where dice can be particularly useful as well, though - when a character's edges, skills, and aspects have absolutely nothing to do with the result of an action or situation. This is when Fortune dice come into play, rolls based on pure luck.

Who Rolls?

Core Wilds Words assumes that players will be rolling more often than the GM, but this doesn't have to be the case. Asymmetric play benefits a game in play by keeping speed higher (usually by treating hazards and the environment differently to characters in terms of agency and roll frequency), but it isn't the only way.

Other Rolls

There are many other situations where dice might be rolled. There's no way we could list them all here, but as a taste you might want to involve dice...

- In damage-based rolls, for when you want unexpected amounts of damage to be dealt.

- In rolls for the potential harm or reward of a situation, such as when determining how much treasure lies within a chest or how many poison darts are shot from a wall.

- In situations where players or GM can use a random table to determine what happens, from a pre-made list of some kind.

Choosing Your Dice

When designing the mechanical side of your game, dice are usually an important component. You might want to go diceless, which Wild Words can definitelysupport, but without direct experience of it myself I wouldn't be able to give much advice on how to do it effectively.

So assuming that you're using dice, you're going to need to decide on the size of them. D6s are a classic for a reason - easy to find and easy to understand - but they're not your only option.

When choosing dice, consider whether results, doubles, and an odd/even split are going to be important. There's a lot you can do with dice, so instead of telling you exactly what you should do, I'll show you a few things I've done myself...

Core D6

The 'Wild Words standard' that powers The Wildsea, dice pools are made of between 1 and 6 D6s. The highest result of a roll is most important, as are doubles. Odd/even results don't matter, and triples give no benefit over doubles. Results are split into three distinct bands - 6s give a triumph, 5s and 4s give a conflict, and 3s, 2s, and 1s give a disaster.

Quarter Eights

Made for Streets By Moonlight, dice pools are made of between 1 and 4 D8s. The highest result of a roll is most important, and the lowest sometimes comes into play too. Doubles and triples add a level of safety that would otherwise be absent for actions. Results are split into three distinct bands, with 7-8 as a triumph, 3-6 as a conflict, and 1-2 as a disaster

Clash

Made for Iron on Stone, dice pools are made of any number of d6s. Highest and lowest results don't matter, but evens and odds do (with evens representing a mech's output and odds a pilot's acuity). The number of evens and odds that can be contributed changes the actions that can be taken. Results are split into two bands - anything above a 3 is a useful result, anything a 2 or below is useless.

Words Before Rolls

Wild Words is designed for fiction-first gaming, and one of the core tenets of this is that the story (and player agency in that story) is paramount. Most dice mechanics assume that a player decides on what they're going to do, and then the dice come into play to tell them how it goes (or an element of the world does something, and the GM or players uses dice to determine the ultimate effect of it)

You can turn this on its head if you do it carefully, as in the Iron on Stone example in the previous column, but I can't fully recommend it.

For Iron on Stone, non-combat scenes are fiction-first but combat is far more mechanical, with a turn order deciding who acts in what sequence, and the result of rolls offering a suite of potential actions to mech pilots.Pool Sizes & Dice Draws

Once you've decided on the size of your dice, you need to set an upper limit on the pools that players (and maybe the GM) will be rolling. Remember, any pool larger than the highest die outcome will necessarily result in doubles. And if doubles are important, the smaller the pool (and the larger the dice), the less likely they are.

You also need to work out where dice are being drawn from in different situations. If the dice are rolled by a player they're probably coming from their character elements, most likely edges, skills, aspects, and resources (pages xx to xx). If the diece are being rolled by the GM, or by a player in a way that's unconnected to their character, you as a designer need to work out how everyone at the table can put together a dice pool quickly and without breaking the flow of play.

Oracle only allows players to roll two dice at a time, but their size can vary depending on the type of action they're taking information drawn from the character sheet. Doubles in Oracle are bad, and high results are good - the larger the dice players roll, the more likely they are to get a high number and the less likely they are to roll doubles. Difficulty in Oracle comes from the GM adding dice to player rolls to break that cap of two, increasing the chance of duplicate results, but there are limited situations in which the GM can pull this off to keep play speed high.Results Bands

The outcome of a dice roll is usually determined by the results band it falls into. Here's an example of a results table that shows off various bands (for ease of reference, this table is drawn from The Wildsea, which uses the Core D6 presentation on the left.)

[TO DO: PUT TABLE HERE]The results bands above are weighted toward bad outcomes (with everything from a 1 to a 5 representing some sort of penalty), with only 6 being a perfect result, but wildsea players tend to be rolling at least 3 or 4 dice as standard. There's also an extra band given for doubles, which the Wildsea uses to bring in narrative-focused twist rules.

This brings up the most important point where results bands are concerned - players will likely be rolling mutliple dice. Even if it looks harsh on paper, it might well be forgiving at the table. Playtest your dice systems!

PENALTY Vs CUT

With a dice pool system linked to non-flexible bands of results, the 'target number' staple of many dice rolling systems is out (though you could engineer it back in if you feel like it). Instead, more difficult challenges in Wild Words are more easily represented by penalty or Cut.

Penalty

This allows difficult situations or poor choices to remove dice from a pool before they're rolled.

Cut

This allows difficult situations or poor choices to remove results from a pool after the dice have been rolled (usually starting with the highest).

The Math vs The Feel

- Penalties are easier to math out for players and GM at the table, but they ultimately result in fewer dice being rolled. And people tend to really enjoy rolling dice.

- Cut is a little more dramatic, a little more cruel. It lets players roll the same number of dice, but by targeting high results after a roll it removes the chance of high-band successes and tends to bring outcomes further down the table. It's a bit gritty, but it's also dramatic - a player knows they were this close to an excellent result, and can bring that into their description of what goes wrong.

Both systems can work here as an indicator of difficulty, but Core Wild Words leans toward the drama inherent in Cut (even if the maths is a little wonkier)

Removed Dice/Results

When using Penalty or Cut the dice or results removed are usually just discounted, lost to the aether - but they don't have to be. Consider adding a new dimension to dice pools by using these discarded dice or results for something new.

In The Wildsea: Storm & Root, characters cut more results when under Scrutiny (the gaze of certain terrifying entities). The results they cut feed directly into the Scutiny system, allowing the GM to take particularly damaging actions based on whether the cut results were triumphs, conflicts, or disasters.ACTIONS

CORE SYSTEM

The Basics

- In its simplest form, an action is anything that a player has their character do within the game.

- Some actions that are difficult, dangerous, or dramatic in nature (as described on the previous page) should likely intersect with the rules in terms of dice.

- Core Wild Words assumes that most actions are freeform in nature - they're decided on and described before the rules come into play.

What Are Actions

Anything a character does during a game.... Well, probably.

For most Wild Words games, anything a character does within a scene is an action. They're assumed to work out if they suit the world and story, unless the outcome or performance of that action runs into the territroy of the three Ds, in which case dice are usually involved.

Harley has her character walk across the room and leaf through a book, looking for the date it was published. This is an action that doesn't require a roll - the information is there in the book, and it won't be that hard to find. In terms of the narrative, it can be assumed that Harley's character will find this information without too much trouble.The example above describes an action that doesn't need to involve the dice. But, if the circumstances were a little different...

Harley needs her character to find the date a particular book was published, and she's only got moments to spare before dire consequences ensue. She describes how her character leafs frantically through the pages - she knows the information is in there, but where? The GM asks for a roll based on her character's skills.Though the action in this second example was pretty much the same, the simple act of finding information is made dramatic by the looming consequences and time-critical nature of the scene.

When writing your rules, make this distinction clear. It helps both players and GMs settle into a good rhythm.

Flexible Actions (Fiction-First)

Wild Words is a fiction-first system at its heart, meaning that it prioritizes story and creativity over mechanics. Even in mechanics-heavy games, the narrative and the choices of those around the table should be dictating when the rules come into play.

This is most easily demonstrated with a flexible action system. A character describes what they're trying to do, and then either they or the GM decide whether that needs to involve the dice and the elements of their character.

Sometimes a player will describe what they want to do based on something their character has access to, and that's absolutely fine. But they should never feel limited to choosing actions specifically because their character is good at something - edges, skills, aspects, resources, all of these should be more weighted toward offering options rather than imposing mandatory moves and choices.

In The Wildsea a specific skill, wavewalk, determines how good a character is at moving through the leafy waves on their own, without the aid of a ship. The action of wavewalking isn't closed off to characters that lack ranks in this skill, they're just a lot more likely to take damage or run into narrative trouble while doing so (due to their inherently lower die results, and wavewalking being the kind of dangerous activity that will almost always require a roll)."HOW MUCH CAN I DO?"

One of the most frequently-asked questions when it comes to actions is how many things a character can do with one of them, or what they might encompass, or how many in-game seconds they represent.

Chuck all of that out of a window for Wild Words, we've got a single critical rule:

An action is long enough to give a player time to make their character shine.

What does this mean? In essence, that every action should be a character doing something interesting, or even just cool or tone-setting. Walking across the room to read a book isn't two actions, it's one - the act of walking isn't particularly cool. Striding across a room with a flourish of your cape might be an action on its own, because it shows off something about that character - but that's up to the player.

Forced Actions (Mechanics-First)

The partial exception to the flexible axtion standard is where impulses are concerned (pg XX). These are specificially designed to encourage (or in some cases require) certain reactions or behaviours from characters, either narratively or mechanically. But even in these situations, the action suggested by an impulse should ultimately be flexible.

In Streets By Moonlight, characters are compelled to interact with certain dangerous occult objects and individuals by their impulses. There isn't a roll to resist this, but instead to determine how well they weather such encounters - they are required, narratively, to engage, but it's up to them to colour the action and describe how this actually comes about.You might have more mechanics-first moments in your game, but try not to rely on them too heavily. They can be great for structuring certain scenes, but they are inherently restrictive.

Adding Action Types

Though actions are a useful catch-all for 'characters doing something', you might want to add a little more structure to proceedings by classifying some types of action as narratively or mechanically different to others. Here are a few pre-made examples of differently-typed actions that you might find helpful when designing the moment-to-moment gameplay of a Wild Words game.

Reactions

A specific type of action that's called for by the GM in response to a character becoming the target of damage or an effect from the world.

Reactions are still quite fluid - a character should be able to decide how they react rather than be forced into a particular specific action - but they're good at representing immediacy and urgency.

In The Wildsea, when a hazard attacks one of the characters the GM doesn't roll. Instead, the GM describes what's happening and asks the player to roll a reaction, stating how they mitigate or escape the incoming attack. A player might have teir character dodge, block, or use the environment in a clever way, but if they choose not to react they just get hit with the full potential force of whatever is coming their wayTasks

Sometimes a time-scale is important. Tasks are longer actions, covering larger periods of time than an average action and allowing characters to accomplish more complex, multi-stage procedures (likely still with a single roll, if a roll is required at all).

Tasks are usually best kept to their own type of scene that allows only tasks to be performed, such as a montage, but this doesn't technically have to be the case.

In Drift, characters that want to explore a station in between journeys will usually do so by using a task. A single player might be able to have their character wander around, find a shop, and purchase something all with a single roll.Sometimes an accomplishment, like building a house, might take multiple separate tasks to complete. This is usually known as a project, and likely has a track of its own that needs filling before completion.

Decisions

Shorter than a usual acton, and far more restrictive, these usually take the form of the GM (or an element of the world) demanding a choice between A or B. A decision might happen at the speed of thought, or need some physical action from a character to be effective.

Decisions are perfect for scenes with stricter rules or a ritualized format to follow.

In The Wildsea, part of a journey is working out which character takes the helm and which goes on watch. These are simple decisions that the players have to make - even if, narratively, the entire crew is gathered around the helm poring over maps and controls, there's still a single player whose character is 'at the helm', and who decides the speed a ship is travelling.Flashbacks

Useful if you want layers to be able to plunge into situations with the minimum of downtime, but you also want the characters to benefit in-universe from the idea of planning.

A flashback action involves a player describing something that their character did in the past that sets up a useful event or moment in the present narrative. Depending on the type of game you're creating flashbacks might not be a thing at all, or they might be freely available to use, or perhaps even tied to the spending of a metacurrency of some sort.

In Rise, a metacurrency (moments) can be spent during combat between nation states to establish that the populace belonging to one player had worked on or achieved something that's secret to the other players, with the action skinned as this project being revealed at just the right time.Actions and Focus

As previously mentioned, when a character has the spotlight they should be able to do something cool.

But how often do they get to do those cool things?

Usually the balance of who gets the spotlight will sort itself out naturally at the table - some scenes might put certain characters at the fore, others a different set. That's the nature of stories. But in a tense action-based scene such as a fight or chase, GMs won't want to leave players out.

To aid them with this, you can use the idea of a focus tracker - an optional system that records which characters have acted, and how many times they've had the spotlight (if you're using actions and reactions, one action is roughly equal to two reactons due to the amound of player agency involved). Here's an example...

- Garth: AARA

- Cho: RRAAR

The A on these tracks stands for action, the R for reaction. Garth hasn't had as much time in the spotlight as Cho, but has had more agency - more self-determined actions. A GM seeing this might give Garth a reaction next, or Cho an action. THis is something for a GM to worry about, but you as a designer to potentially suggest.